|

Photographs (left to right): Ocean, San Diego Beach, California; California Desert Ocean Sunset; San Diego Beach, California

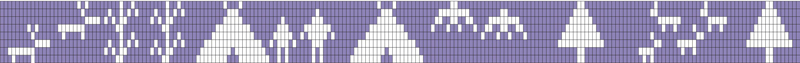

Wampum Belt Archive

Anishinaabe

1820

Original Size:

Est. Beaded Length: 33.0 inches. Width: 4.0 inches. Length w/Fringe: 57.0 nches. Beads: Glass

Beaded Length: 33.0 inches. Width: 4.0 inches. Length w/Fringe: 57.0 nches. Beads:

Columns: 207. Rows: 8. Beads: 1,656.

Materials:

Warp: Deer Leather. Weft: Artificial Sinew. Beads: Polymer.

Description:

During a ceremony marking the 200th anniversary of the signing of Treaty 22, Oakville Mayor Rob Burton announced his intention to have a permanent monument erected in Oakville to acknowledge the treaty lands.

“It is my hope that we can create a permanent monument of this exchange in Town that honours this exchange and the ongoing relationship we have with the Mississaugas of the Credit First

During a ceremony marking the 200th anniversary of the signing of Treaty 22, Oakville Mayor Rob Burton announced his intention to have a permanent monument erected in Oakville to acknowledge the treaty lands.

“It is my hope that we can create a permanent monument of this exchange in Town that honours this exchange and the ongoing relationship we have with the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation,” said Mayor Burton.

The announcement came during a wampum belt exchange, a ceremony in which Mayor Burton and Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation Chief Stacey LaForme acknowledged the anniversary of the signing of Treaty 22, which encompasses the lands at 12 Mile Creek and 16 Mile Creek in Oakville.

The wampum belt exchange has traditionally marked events, alliances and kinship between different peoples.

Treaties

On February 28, 1820 Treaties 22 and 23, referred to as the “Credit Treaties”, were signed and the Crown acquired the reserve lands, which had been set aside in the 1805 agreement. According to the terms of Treaty 22, the Mississaugas acquiesced to the Crown’s demand for lands at 12 and 16 Mile Creeks along with northern and southern portions of the Credit River Reserve.

Treaty 23, negotiated later the same day, involved the central portion of the Credit River Reserve, along with its woods and waters.

Treaties 22 and 23 were signed, once again, by William Claus, Deputy Superintendent General of Indian Affairs on behalf of The Crown, along with Mississauga Chiefs Acheton (Adjutant, Ajetance, “Captain Jim”), Woiqueshequome (Weggishgomin, Okemapenesse, “John Cameron”), Novoiquequah, Paushetaunonquitohe and Wabakagego. The agreements was witnessed by James Givins, Superintendent of Indian Affairs, Alexander McDonell, Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs, William Gruet, Interpreter for the Indian Department, D. Cameron, N. Coffin, and members of the 68th Regiment.

The Credit Indian Reserve lands along the Credit River were retained by The Crown as the Credit Indian Reserve until March of 1846 when the lands were surveyed and put up for auction.

All five of the agreements and treaties involving what is now the City of Mississauga had two constants: all were signed by William Claus on behalf of The Crown and Mississauga Chief Okemapenesse/Weggishgomin/”John Cameron” on behalf of the Indigenous Mississaugas.

Understanding treaties and concepts of land use is complex and is a key component of reconciliation. Governments often interpreted treaties as legal documents that ceded or surrendered land – a type of real estate purchase of Indigenous lands – and as such a surrender of Indigenous rights and claims to land.

For Indigenous peoples, treaties were sacred covenants of trust, and that the true character of the agreements is not found in the legal descriptions, but in what was said during negotiations. Treaties were often accompanied by traditional ceremonies, such as the smoking of pipes or an exchange of wampum belts. The Indigenous view, treaties are seen as instruments of sacred relationships between autonomous peoples who agreed to share lands and resources. Seen from the Indigenous perspective, treaties do not surrender rights; rather, they confirmed Indigenous rights.

Indigenous peoples regarded the promises outlined in the treaties as sacred and enduring; however history has shown that Crown representatives did not. Negotiations were often conducted in bad faith. In regards to the Mississaugas, they entered into treaties with The Crown seeking mutual respect and co-operation, although as shown by Chief Quenepenon’s remarks in 1805, the Mississaugas were already wary of broken promises. Over the many years since these treaties were signed, the relationship between The Crown and the Indigenous Mississaugas have been eroded by colonial policies that were enacted into laws. Understanding treaties rights and seeking to resolve specific claims is a beginning towards understanding and honouring treaty obligations.

References

200th Anniversary Treaty 22. 2020. https://www.oakville.ca/town-hall/news-notices/2020-mayor-s-news-archive/wampum-belt-exchange-marks-200th-anniversary-of-signing-of-treaty-22/

Treaties 22 and 23. 2020. https://www.oakvillehistory.org/uploads/2/8/5/1/28516379/treaty_treaties_22_and_23.pdf

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|